Later this evening, Benjie Weinberg called me up and demanded that we go out drinking. I might have preferred to stay home and stay out of trouble, but I agreed. He told me to meet him at Paradox Alley.

Paradox Alley was in a basement, on West 111th and Broadway, underneath the Le Broadway pizza parlor. The Alley was decorated in a vaguely Californian style, with red-tile floors, white-stucco walls, copper-potted hanging plants, and arch-topped Spanish-looking doorways. The name Paradox Alley was justified by the Escher prints hanging on the walls, one over each booth.

"Escher prints?" Benjie snorted. "What a cliche, so passe, don't you agree, Billy?"

"I agree, Benjie," I said (though in fact I did not agree.) We met up with Frosty and Shig, and one thing led to another. We actually didn't do very much drinking. We went back to Shig's dorm room to smoke some hash, and then Frosty called Tammi and somehow he got the assignment to help some of the girls from Eight Hewitt with their Art History midterm. Tammi was not one of the women who showed up at the Beau Parlour on the first floor of BHR. This didn't deter Frosty: he blathered doubletalk long into the night. Shig and Benjie and I got bored and wandered out of the Beau Parlour. The BHR corridors (on the first floor) were long and austere and drafty, with lots of columns in the Doric order, much like the corridors at the British Museum.

Kylie Tomczak was walking down the corridor, carrying a can of Tab and a stack of art books. She was wearing oversized pajamas with mutant pink bunnies leering ravenously at each other all over the fabric. Her hair was blinking red and blue like a Budweiser sign. There appeared to be some sort of rubbery green clay plastered all over her face. "Hey, Kylie," I said, which way to the Elgin Marbles?" Frosty had just been talking about the Elgin Marbles.

Without stopping, she said, "Turn left at the end of the corridor."

We turned left at the end of the corridor, and found ourselves back in the foyer. Benjie W and Shig asked the guard at the front desk if it was okay to use the table-soccer table. In spite of a large sign that read NO FOOSBALL AFTER 11:30 P.M., the guard said "yes." (By now, it was after 4 a.m., so maybe the guard figured it was that it was now really, really early in the morning rather than really, really late at night.)

Shig and Benjie idly twirled the handles of the table-soccer machine, making the little plastic men rotate through millions and millions of bicycle kicks. I popped a quarter into the soccer-table's coinbox and several table-soccer balls (like a ping-pong ball, but slightly heavier) rolled down into a bin on the side of the machine. I dropped the first ball in the centre of the table. Shig's striker promptly kicked the ball way too high, a foot or more above Benjie's goal. The ball bounded into the TV lounge and I ran after it.

Tammi Honig was sitting in the TV lounge, all by herself. Her art-history notebooks were sitting on the sofa next to her, but right now Tammi was busy watching a rerun of The Donna Reed Show. Tammi's hair had turned into a mass of medusa-like snakes, and there were a couple of carnivorous dinosaurs crawling across her bizarre blood-red Chinese silk dress. I thought she looked adorable.

Tammi smiled a carnivorous smile at me. She raised her arm and motioned for me to sit next to her.

I sat down, and snuggled up cautiously. The snakes on her head were softly humming a Sammy Hagar song entitled "Red."

"This is a really depressing show," Tammi said. "The heroine is this really strong, sexy, beautiful woman, but she's stuck in a totally cheerless world, in a frigid marriage with a brainless, sexist, condescending doctor."

The beautiful woman (Donna Reed, a.k.a. Donna Stone) had enchantingly mischievous eyes. You could tell she was secretly cooking up some incredibly devious mayhem. "Why is she wearing that strange underwear under her normal-looking dress?" I asked Tammi. Donna Reed was wearing a bizarre mechanical undergarment that made her breasts jut up at an unnatural 45- degree angle.

"I think her doctor is heavily into S&M," Tammi said. "We never actually see the two of them fucking, though, so we can only surmise, of course."

"Why doesn't she leave, if things are so bad?" I asked.

"It's the 1950's," Tammi said, "not the 1980's. She can't leave. Course, the 80's will suck, too."

"You don't know that yet, Tammi."

"No, Billy, I do know that, already, without having to live through the 80's," Tammi said. [The 70's were such a dreary era that, as early as 1977, people began thinking of the 80's as having already started. Little did they know that things would get even drearier after 1980.] "There are some awful, awful things coming," Tammi continued. [Tammi was right, it turns out.]

The plot of the show was incomprehensible. As near as I could make out, Donna was apparently trying to dose her husband's Jello with LSD. A shorter, younger woman with a triangular face (as opposed to Donna's square face) kept interfering with Donna's scheme. This woman was wearing the same kind of bizarre undergarments as Donna. "Who's this?" I asked.

"Ostensibly, it's Donna's and the doctor's daughter. Nobody is altogether sure who the father was, though," Tammi said. "The biological father, that is."

"Why is she wearing the same funny underwear as her mom?"

"Incest," Tammi told me. "The father has her under his sexual thrall, and he's using her to defend himself against Donna. If you go ahead and marry Edie, don't act like this asshole. I will come back from the dead and kill you if you do! You want some Zoom?"

Tammi handed me a bottle with some large brown pills in it. The pills smelled like tannic acid. "What are these?" I said.

"This is Zoom," she informed me. "A natural stimulant, made from the bark of the guarana tree, which is a special tree found only in the Amazonian rain jungle."

I decided it would be pointless to take any Zoom, but I still asked her, "Does it really work?"

"I guess so," she said. "I'm still awake. Of course maybe that's just because my stomach hurts." She started rubbing her stomach.

I reached over and started rubbing Tammi's stomach for her. "That feels nice," she said, "though it's probably not making any difference."

After 60 seconds of stomach-rubbing, Tammi said, "I've studied enough Classical Art for one lifetime."

Benjie W and Shig had finished playing table-soccer. I didn't see them anywhere, so I just dropped the lost ball (which I found in Tammi's hand) into one of the goals. We could hear Frosty's voice emanating plangently from the Beau Parlour, still lecturing Lizzie's friends about Classical Art. Benjie and Shig were staring at the fibers on the carpet. I joined them. The carpet turned out to be amazingly beautiful: the noble fibres of the acrylic glittered in all the colors of the rainbow (and some colors not found in the rainbow.) The scene reminded me a little of a cypress grove in the Everglades, except that here everything was dryer and more transparent and there were fewer mosquitos.

Eventually, Frosty concluded his discourse and let the five anonymous girls go back to their rooms. (They all got A's on the exam.) The four of us headed down to Riverside Drive. We strolled along the leaf-strewn hexagonal-tiled esplanade at the upper edge of Riverside Park.

A delicate pearly-gray haze hung over the Hudson River. "See that fog?" I said enthusiastically. "That's part of a sphere of thoughts, dreams, ideas, and whatnot created by the collective mental processes of all us sentient beings here on earth. You can only actually see it right at dawn, but it's always there." (I was bullshitting, of course the haze was just a normal morning fog.) "This is the NOOSPHERE!"

"The know-oh-sphere?" Benjie chuckled. "That sounds like a joke to me!"

"How come there's no O?" Shig asked. No one answered Shig's question.

"This is a dumb joke, guys," Benjie W whinged.

"Weinberg, It's not a joke," Frosty said. "The earth is surrounded by many spheres." He pointed down at a small boulder. "The lithosphere: a sphere of rock." He pointed over at a shrub. "The biosphere: a sphere of living matter." He pointed overhead at the sky. "The atmosphere: a sphere of gas." He pointed even farther overhead. "The ionosphere: a sphere of ions." Finally, he pointed (a bit too solipsistically) at his head. "The noosphere: a sphere of knowledge."

At this point, Benjie W stepped into a lump of matter left behind by a passing mammal, probably a dog, maybe a wolf, possibly a coyote— but in any case definitely some sort of canoid.

"You got some dogshit on your shoes, Weinberg," Shig pointed out.

"They're not my shoes," Benjie W chortled. "They're Benjie S's."

"Oh yeah," Frosty added, "I forgot a sphere: I forgot to mention the coprosphere, also known as the cacasphere: a sphere of shit."

*****

We descended a stairway into the main part of the park. We stood there and gawked at the scene. Purple-skinned joggers ran mechanically along a measured mile, leaving little clouds of sweat behind them Frosty led us down a slope overlooking the freeway and the river. (From most of the park, the freeway was audible only as a subtle, continuous, oceanic murmur.) Traffic was moving pretty well, on the freeway and on the river. (Several coal barges were riding the tide up to Albany.)

Benjie W pointed at a huge cylinder on the other side of the river, in Edgewater, New Jersey. The cylinder had the mysterious word HESS painted on it. He shouted, "HESS!"

"'HESS,' man, 'HESS!'" Frosty replied. "You know what I mean, 'HESS.'"

"'HESS!' I dig. I dig totally!" Shig exclaimed. I remained silent.

Frosty led us through a square opening into a tunnel underneath the park. The tunnel was 20 metres wide by 4 kilometres long, and had a disused railroad track running through it. I'd never really thought about the railroad before, even though I knew intellectually that it was down there somewhere. I had read Robert Caro's colorful account of Robert Moses' rebuilding of Riverside Park in The Power Broker. I had seen the railroad viaduct running alongside the freeway and Riverside Drive viaducts over the Hudson View Diner and Marginal Street. I had also seen the huge switching yard between West 59th and West 72nd Streets. I had occasionally noticed grate-topped things in Riverside Park that looked a lot like ventilating ducts. But I had never really realized that there was really was a railroad underneath the Park.

We headed north along the railroad, which was not dissimilar to the similarly disused line that ran near my house in New Hampshire. There were windows every 50 metres or so overlooking the river, so the tunnel was not particularly dark.

After a while, we sat down on the tracks to rest. The rugged granite and concrete walls of the tunnel were covered with manic subway-graffiti. The graffiti was technically surprisingly sophisticated, because most of the graffiti-writers were ill- behaved but self-conscious upper-middle-class kids who had ready access to art lessons, museums, et cetera. (Some of the kids lived in Morningside Heights. They were nice, harmless boys [rarely girls] who could often be seen skateboarding up and down the wheelchair ramps on campus: gentle creatures who liked to think of themselves as outlaws and desperados.)

I was admiring a bubble-style red-and-green graffito by BLOOD 172. Blood 172 was a promising artist, who was heavily influenced by Roy Lichtenstein. Blood 172 used an awful lot of polka-dots.

Suddenly, the green polka-dots started to swell out from the wall, as if the green paint had been transubstantiated into algae. And then, red blood started spewing out from the wall, first seeping through the portion that had been spray-painted red, and then pouring in a torrent through any and every chink in the wall of the tunnel. The blood quickly started to fill the tunnel. Soon, we were waist-deep in rancid, stale blood. I looked around to see what my friends were doing.

Frosty and Shig were facing away from me, reading a day-old newspaper that Frosty had salvaged from his briefcase before it was submerged. They seemed to be totally unconcerned about the flood.

Benjie W was sitting next to me. Like me, he had been staring at the Blood 172 graffito. He was quietly singing the "Beer Barrel Polka." He stopped singing and said, "That's a cosmic song. It's about a barrel of beer, and the beer is immanent throughout the universe of the song, but the beer never actually appears. Just like god is immanent in our universe, but never appears."

By now, the blood was up to our chests.

I whispered confidentially into Benjie W's ear. "Weinberg, I have this bizarre hallucination that the tunnel is filling up with blood. I don't know what to do about it."

"Well, McEwan," Benjie whispered back. "You have two choices. One, swim out of the tunnel. Two, psychically will the blood away."

I tried to swim, but I was too stoned. So, I had to try psychically willing the blood away. After a surprisingly small amount of mental effort, the blood began gurgling down through the crushed-rock bed of the railroad. Our clothes instantly dried, and the blood-stains magically disappeared.

Benjie was still humming the "Beer Barrel Polka."

"Why this sudden fascination with the 'Beer Barrel Polka?'" I asked him.

"Because of those polka dots on the wall, of course," he explained.

*****

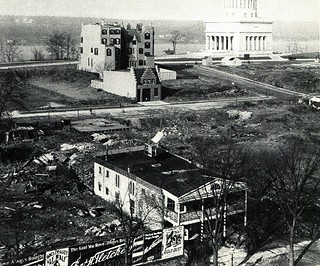

We climbed a stairway behind some tennis courts and found ourselves near Grant's Tomb.

"Who's buried in Grant's Tomb?" Benjie asked.

"Grant, of course," Shig replied prosaically.

Read an excerpt (set after the Twilight Jones & the Elvis Clones gig)

Read even one more excerpt (set during the 1980 Democratic National Convention)

Read one final excerpt (this time on Xlibris.com)

State Senator Kathleen Sgambati's unofficial campaign theme song "Sgambati to Love"